Article

HAIRWORK JEWELS

HAIRWORK JEWELS

ANNE SCHOFIELD ANTIQUES

Of all the materials used in jewellery, I find the most intriguing to be human hair. It memorialises loved ones passed, and is a keepsake to be truly treasured.

I have recently acquired a superb collection of mourning jewellery made from human hair, the centrepiece of which, is perhaps the most interesting example that has ever found its way into my possession.

It is designed as a large bow applied to an engraved gold base set with garnets. A chain hung with a detachable gold pendant section terminates in a gold locket set with a central garnet decorated on four sides with plaited human hair. Inside the crystal locket on the back is more woven hair surrounded by decorative gold carving.

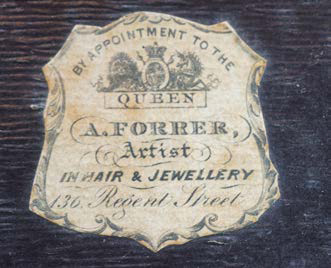

The brooch has been preserved in mint condition in its original fitted case labelled;

‘A. Forrer, Artist in Hair and Jewellery, 136 Regent St, By Appointment to the Queen.’

Forrer was working at this address from 1840 to 1860, and exhibited at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851 where his Hair Jewellery display created great excitement.

Hair brooch mounted on 18ct. gold and set with garnets

Spectators were impressed not only by its beauty but by the incredible ingenuity in its manufacture. If you were skilled at handiwork you were even encouraged to try it yourself, with instructions provided in publications such as ‘The Jewellers Book of Patterns in Hairwork’, published in London in 1864.

I know how highly skilled these hair artists were as I was once asked to fit a lock of hair from a dearly departed daughter into an antique gold locket. It was extremely difficult to fashion it into a simple coil, let alone an intricate plait, but I eventually managed to tie it with a gold thread to fit the inner case perfectly. The client was so delighted he asked me to do another three!

Forrer’s marvellous hairwork brooch came to me accompanied by a portrait miniature on ivory labelled ‘Lady Hindmarsh’, the wife of the first governor of South Australia, Rear Admiral Sir John Hindmarsh, who held office from December 1836 to July 1838 after which he was recalled to London.

There was also a second portrait miniature of John and Susannah’s daughter, Mary Hindmarsh wearing a necklace of plaited hair. Mary married George Milner Stephen, the Colonial Secretary of South Australia from 1838 – 1839, later appointed Acting Governor.

It is important to remember that before the mid 19th century there were no photographic images to remind people of a departed family member, relative or friend. Only very wealthy people could afford hand-painted miniatures, let alone golden adornments made of hair.

Lady Susannah Hindmarsh returned to England and died on the 2nd April 1859. It was then that the mourning brooch was made using her hair. The collection included another exquisite lyre-shaped gold brooch made with human hair, again in its original case by Antoni Forrer.

The wearing of mourning jewellery had become widespread in the 17th and 18th centuries. When the famous diariest Samuel Pepys died in May 1703 he left money in his will to have mourning jewellery made. In fact, he bequeathed no less than 123 rings to his friends and family!

The fashion for mourning rings, pendants, brooches and necklaces, achieved almost cult status during the Victorian era from 1837 to 1901. It peaked after the death of Prince Albert in 1861, and echoed the widowed Queen’s protracted period of mourning.

In 2022, I made a donation of antique jewellery to the Powerhouse Museum including several rare examples of 18th and 19th Century mourning jewellery. One of these pieces was an eye miniature surrounded by pearls and plaited human hair.

Some people find it macabre, but I believe mourning jewellery made from this most personal material to be the most evocative of items. They are a lifelong memento of a loved one, worn on the body, close to the heart.

info@anneschofieldantiques.com

+61 2 9363 1326